I’ve been thinking a lot lately about the idea of human-centric infrastructure. After going deep into Charles Marohn’s Strong Towns a few years ago, I’ve been really contemplating what a “better” city looks like – not just in terms of clean sidewalks and new buildings, but how cities can, through their design and infrastructure, intelligently improve how we live, work, and play with each other.

That’s why I was excited when I was able to sit down with Ari Isaak, the founder of Photometrics AI and Evari GIS Consulting. After talking to Ari, it’s clear that he isn’t just optimizing lights—he’s answering the question I’ve been wrestling with, how does a city optimally function, at the most granular level. From safety and sustainability to neighborhood identity and community resilience, Ari is exploring what it would mean for public infrastructure to meet us where we are, both in physical space and in real human need.

We talked about where he thinks resilience really comes from, what government gets wrong (and right), and how one light at a time, we can make our cities more human.

I’m primarily interested in the concept of resilience – whether personal, communal, or societal. What does the concept of resilience mean to you?

I had to think a lot about this one – this is good!

I’ll tell you what, I’m not a fan of the idea of the self-made man. There’s a famous sculpture of “the self-made man” where he’s chiseling himself out of marble, and I don’t really think it’s that accurate.

I think our strength and resilience comes from the people around us, and that security net is what enables us to take risks and make decisions. If you’re worried about where your next meal is going to come from, if you’re worried about the basics, it will be hard to take any sort of risk since that’s the top thing on your mind.

I think resilience comes from family, friends, and the world that you have around yourself that enables you to make it through any challenge that comes your way.

Resilience is born as a result of having the safety of a social sphere around you that lets you bounce back from challenges and risks more easily?

Yeah, whether it’s just taking risks in the first place, or overcoming challenges, or just having the ability to fail. You must have people that love you even after you fail! So I really think resilience comes from all of the people around you, who may not say it explicitly, but believe in you.

And would you say that you have that resilience safety net around you?

Oh, absolutely. When I started both companies, I couldn’t have done it without the support of my wife. She was going to experience either the benefits or the challenges right alongside me.

When we launched Evari GIS Consulting, she was a college professor in Irvine. She was commuting from San Diego to Irvine twice a week, and at the same time, I landed a small contract. That left us with a big question: Should I stay at my government job at the Port of San Diego, or should I go all in on the business?

We talked it over, and she said, “Go for it.” At the time, we didn’t have kids yet, and we were living in a one-bedroom place. In the end, it turned out to be a good bet—but none of it would have been possible without her support.

In a previous interview, Bill Simon said that it always seemed to be less risky to start his own company and bet on himself than to work for someone else – since he would have more control over his own career. Would you agree with that?

I generally agree with that. But I think the idea of becoming an entrepreneur is seen as more risky than it actually is. There’s this concept that losing a dollar hurts ten times more than the joy of making one. I think that holds a lot of people back.

We have safety nets—unemployment, family, personal savings, whatever—and while you don’t want to tap into the safety net, that security also enables me to invest in an idea that might not pay off for four or five years.

I also agree that there’s a false sense of security in having a job where someone else pays you. Unless you work for the government—but even in the government these days, that’s not necessarily secure.

You’re currently the founder of an AI startup, Photometrics AI – but you’ve previously founded another company, Evari GIS Consulting, Inc. Can you talk a little bit about your experience running your own company?

Evari GIS Consulting is a GIS consulting firm that found a niche in supporting street lighting conversions. When a major city wants to convert its streetlights to LED, they need to know where every light is and what type it is.

A lot of the time, these projects are funded through ESPC (Energy Savings Performance Contract) agreements. Essentially, the contractor guarantees the savings upfront—before the job is even done. It’s like getting a home remodel where the contractor guarantees your house will increase in value by $100,000. And then, the project is financed through that model.

To make it work, cities need detailed data: what streetlights are out there, their wattages, energy usage, things like that. That information allows them to calculate the new lighting plan and determine the energy savings. Our job is to collect that data. We’ve done this in cities across the U.S., including Honolulu, Chicago, San Francisco, Oakland, Philadelphia, and Boston.

Beyond just meeting the financial requirements of these contracts, GIS data is critical for managing the construction process. Crews need to know exactly where each light is, which lights to load onto trucks, where to replace them, and a ton of other things. We’ve built entire systems to support this process, including capturing before-and-after photos as part of the audit and linking everything back into GIS data.

Evari GIS Consulting also uses AI to analyze these photos, helping cities better understand and manage their street lighting infrastructure.

What drove you to start Photometrics AI?

When I was doing this work across the United States, I realized something and I’m just going to say it: they’re doing it wrong. There’s a part of this process that isn’t working, and I was in a unique position to fix it.

So right now, cities design what are called typical layouts—cookie-cutter lighting plans based on standardized guidelines for road design. These manuals dictate things like road width, bike lane dimensions, sidewalk placement, and the type and spacing of streetlights. The idea is that engineers can use these templates when designing new roads or developments.

But in reality, cities weren’t built this way. Many older streets don’t follow a standard pattern. In some areas, like North Park, we have a grid layout. In others, we see sort of dendritic street patterns with cul-de-sacs, and then there are major arterial roads and stroads.

The way lighting is currently designed follows these cookie-cutter templates rather than adapting to the actual street layout. Cities like San Diego, Phoenix, or Oakland are broken down into a handful of typical layouts—maybe 20 for a city with 100,000 streetlights. Then, using Excel, they extrapolate the lighting design for the entire city based on those few templates.

The problem is it misses critical details. It doesn’t account for whether a road curves left or right, whether a light is mounted on a mast arm, whether intersections don’t meet at right angles, or whether there’s only a sidewalk on one side of the street.

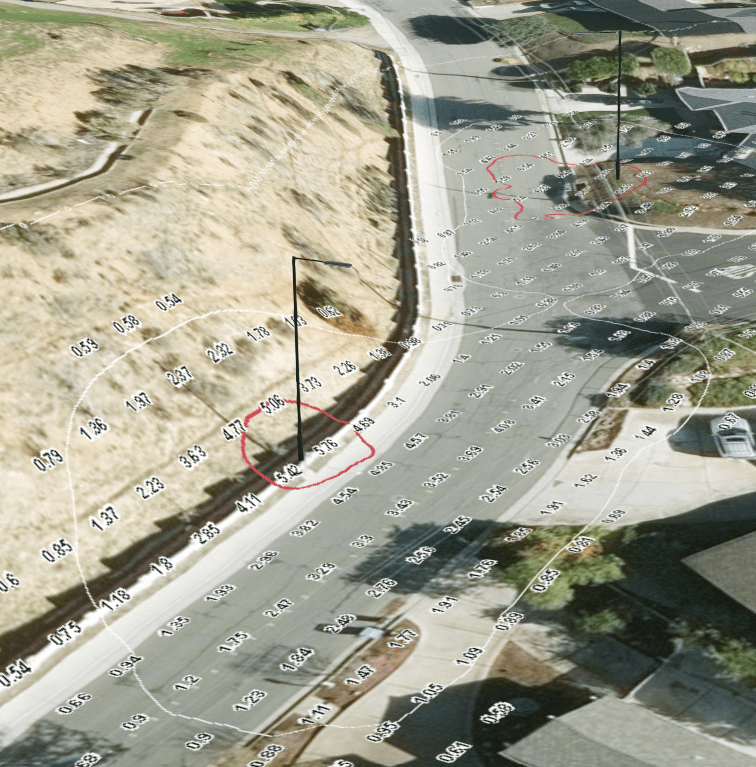

So my idea was to bring the lighting design process into GIS—so we can actually see where the light falls on the street. We built this tool within Evari GIS Consulting, called EvariLUX, and it’s now being used across the country. It was a huge investment five years ago, and it’s just now paying off.

Now, Photometrics AI takes this concept one step further. Today, many streetlights are connected to control systems. So the question becomes: How can we tap into those systems and get the lights to perform exactly the way we want?

I developed a patented concept called the Target Lighting Layer. It allows cities to specify exactly where they want light to go—down to precise illumination levels. For example, 7 lux on the street, 4 lux on the sidewalk, 1 lux on front yards, and 0 lux on the windows of your house.

Instead of running every light at 100% brightness, our system calculates the optimum dimming level for each one—maybe 85%, 72%, or whatever is needed to meet the lighting goal. Using GIS and AI, we calculate the exact dimming level for every light in the system, which results in about 25% energy savings.

But the benefits go beyond just energy savings. A city like San Diego spends $4 million a year on electricity just for streetlights. With our system, that could drop to $3 million. Even bigger savings come from maintenance—running lights at an optimal, lower level extends their lifespan, reducing failure rates and replacement costs. Most streetlights are designed to last 50,000 to 100,000 hours at full power. By running them at a lower wattage, we can significantly extend their lifespan.

Ultimately, our goal is to bring precision to an industry that has relied on rough approximations for too long. The standard approach of dimming all city lights by 30% after midnight is a step in the right direction, but it’s not truly data-driven. We use math and AI to calculate the optimal dimming level for every light, making street lighting smarter, more efficient, and more cost-effective.

And that’s what we’re doing.

And how has the industry received this so far?

It’s definitely an uphill push. There are a few key challenges. When you’re optimizing light levels, the question comes up—is there really a business here? Is lowering lighting levels really a venture-scale opportunity?

There are also obstacles when it comes to getting new rates from utilities, and then you have multiple players involved in the government space. It’s not just one department making the decisions. The people managing energy and utility bills aren’t the same as the ones maintaining the streets. The police, who are concerned with lighting’s role in crime prevention, are separate from transportation safety teams, who care about encouraging people to use crosswalks. It’s a mix of different priorities across multiple departments, which makes progress more challenging.

What we’re hoping to do is keep our costs low enough that the decision becomes obvious for any one of those stakeholders. We’ve worked to calculate the average direct financial benefit of implementing Photometrics AI for each of them, and our pricing will come in well below that threshold.

For example, if adjusting lighting levels could reduce crime by even 1%, that translates to about ten dollars per light per year in savings for the average local or state government. Our goal is to come in well below that—say, at two dollars per light per year. That way, the police department decision-maker we’re talking to sees an immediate benefit.

But then, they might need to check with the energy department, and then they might need to check with transportation safety, and so on. So yeah, it’s challenging, but we’re making the case as clear and compelling as possible.

It’s interesting you say that, though. It echoes your opening point about how resilience is community-oriented and not just one person in a vacuum. The product you’re selling can be painted that way, too! The benefits of street lighting are community oriented, and it sounds tough to sell and impress the benefits of improving street lighting to just one person in a silo.

I want to preface this by saying that I’m a capitalist. I believe in capitalism, I believe in making money, I believe in all of that. But I also believe it’s okay for us to work together on things that benefit everyone, and that doesn’t always have to be financially driven.

The classic example is the fire department. People used to have to buy fire insurance, and if you didn’t have it, the fire department wouldn’t come. So if Joe had fire insurance but Steve next door didn’t, and Steve’s house caught fire, the fire department would let it burn. But eventually, that fire would spread and take out Joe’s house too. At some point, people realized it just made more sense for everyone to pitch in and create a public fire department.

I have no problem with that. We can work together on things, and that’s okay.

There’s this attitude that working for the common good is somehow a bad thing, and I don’t understand it. We can improve street lighting across the entire U.S., and that’s not a bad thing.

In a previous interview, I talked to Sam Dettman, who was running for a Trustee position in his city in Wisconsin. We talked about how resilience can be built into the way a city is designed – the character of the architecture, how roads and neighborhoods are designed, and even the interplay of the natural and urban environments can influence how we interact with our cities and communities, and can create a resilient environment. Would you agree with that? How does street lighting play into that?

So both answers are yes, in my opinion. We absolutely design and choose the neighborhoods we live in, the places we work, and the places we go out to dinner because those spaces make us feel a certain way and support the kind of activity we want to do there.

If you want to live on a street where your kids can play catch in the middle of the road, you move to that kind of neighborhood. Downtown Manhattan probably isn’t the right spot for that.

The infrastructure we build is purposefully designed to support our lives and to discourage behaviors we don’t want. Now, that doesn’t always work. Sometimes people want to do something badly enough that they’ll ignore what the infrastructure is telling them. So it’s not a perfect system, but it is one of our most powerful tools—and we should design our cities and our spaces to support the way we want to live.

Streetlights are a part of that. We should be using lighting to encourage the behaviors and activities we want to see—not with a one-size-fits-all solution, but in a way that’s dynamic and responsive.

One thing I haven’t mentioned yet about Photometrics AI is that, because it uses AI, it can figure these things out in seconds. Photometrics AI can quickly calculate the optimum lighting performance for a specific setting. That means we can do things like adjust lighting for Halloween. That doesn’t need to apply everywhere—maybe it only affects quiet, single-family neighborhoods where the parcel sizes make it good for trick-or-treating.

You’re probably not going to walk a mile between houses, so we know where those neighborhoods are—and we can use light to encourage that kind of activity. Our kids should be able to go out and trick-or-treat safely, and we should use lighting to support that. We should be treating the street like a place for walking kids, because for that night, it is.

That’s a good point.

I think a lot of people only notice when there’s an absence of street lights, or one is broken. If things are working, most people tend not to think about it. Can you talk about how you educate people on that streetlight improvements are actually necessary?

I’d say when I talk to people about Photometrics AI, a lot of them say, “Oh, I never even thought about that.” And I’m like, well, they’re everywhere. Streetlights are on every street. There’s about one streetlight for every two houses in the U.S.—so roughly one for every five people. They’re freaking everywhere, but people often confuse them with traffic signals.

I’ll hear things like, “Oh, I want the red light to go away. Isn’t there some sort of motion thing?” And I have to say, “That’s not what I do.”

Streetlights exist to bring a little bit of the day into the night, but people don’t really notice them unless they’re not doing what they’re supposed to. When a streetlight’s out—or on during the day, which happens constantly—that’s when people pay attention. And that’s part of the challenge I’m trying to solve.

Every single day, there are lights that are on when they should be off and off when they should be on. They’re too bright, shining into people’s windows while they’re trying to sleep, or they’re wasting energy lighting up front yards that don’t need it. What we need is much more precision in how street lighting is managed.

But to go back to your question—no, people really don’t think about this stuff much. When I go to investor events and explain what I’m working on, they’re like, “Wait, what? Streetlights? How’s that a business?” So I have to do a little bit of education. I explain there are different types of lights, we can dim them, we can place them more strategically. But yeah, it’s something most people just don’t pay attention to.

That sounds challenging, since you have to educate so many people on why this actually is a problem, and it’s a problem with infrastructure that people don’t often think about.

Yeah, and it takes a little while. I’m not selling a new energy drink.

It’s not hard to explain, but when I say I’m optimizing street lighting so it falls on the street and not in front yards, I don’t think it really clicks for most people. They don’t know what’s possible. They assume all lights are the same—like there are three kinds or something. But no, there are hundreds of different types. You can change their color, their distribution, you can dim them, and many are connected to control systems.

And when I talk to people who are already in the industry, they’re often pretty entrenched in the way things have always been done.

That’s why I think my best angle is to reach Public Works directors. They’re not as locked into traditional processes, and they actually have a broad understanding of how street lighting fits into the bigger picture. They know what maintenance costs look like, they know how much it costs to buy a new fixture, they understand the impact on crime, and how lighting affects transportation safety.

So that’s really who I want to work with. They have the right perspective and the authority to think holistically about lighting and how it can be done better.

What does the future of street lighting look like to you? The future of city design?

They should all work together! In our hyper-connected world, it’s completely unacceptable that government is still slow to adapt and build systems that function as seamlessly as, say, an iPhone.

An autonomous car should have everything it needs to get a person to their destination safely—whether that means streetlights illuminating properly or pedestrian systems ensuring people can cross the street safely. We must do a better job. In my mind, this really comes down to government. Government moves slowly, and utilities that manage streetlights also move slowly. But they have to work together much better. Private industry would never tolerate the kind of inefficiencies that are just accepted in government.

I’ll give you an example. At one point, I was talking to someone about street paving. He was in charge of digging up asbestos pipes, and I suggest coordination so that street paving happens after the asbestos pipe work is done—not two months before, only to dig it all up again.” And his response was, believe it or not, “You’re going to make my job harder.”

That’s exactly the problem. He was in a different department, working on his own timeline, with no regard for the bigger picture. And that kind of disjointed thinking is everywhere in government. We have to do better.

The future will belong to cities that make innovation a priority—those that move away from entrenched interests and start working with smaller, more agile innovators. Cities need partners who can orchestrate and facilitate activities in public spaces more effectively.

In terms of lighting, it should change based on when and where it’s needed. We need the right light in the right place at the right time. Halloween is one example, but what about during a major car crash? Could a 911 call trigger a change in street lighting? If emergency responders receive a dispatch code with a crash location, could the lighting automatically adjust to help them? Light could be critical when performing CPR or assisting an injured person, and while emergency vehicles have their own lighting, there’s no reason streetlights couldn’t dynamically adapt to provide additional support.

We’ve already transitioned from legacy technology to LEDs, and many of those LEDs are now on control systems. The next step is to evolve. We need to innovate and align street lighting with how we actually use it in the modern world.

What’s next for you? How could someone reading this blog potentially help you?

I’ve been thinking a lot about this. You can reach out to me directly, but you can also contact your Public Works director or send a comment to your city or utility—whoever manages your streetlights—and say, “I think this guy is onto something.”

Maybe you’d really like it if the light didn’t shine in your window, and you think this approach could make sure that doesn’t happen across the entire city. Plus, you’ll save energy because right now, you’re spending money and energy to put light in someone’s window. So, can we not do that? Can we just not? He doesn’t want it.

So yeah, recommend that they reach out. I’d love to talk with anyone across the U.S. or even globally. We’re already having conversations with folks in Europe about this idea.

As for what I do every day…I read a blog post the other day that said, “If you’re a founder, you’re either building or selling. There’s nothing else.” And that really resonated with me.

I switch between those two things. I make sure our MVP is up and running, I create videos for LinkedIn to share what we’re doing, I reach out to Public Works directors I’ve worked with before, and I build partnerships with private companies that can help us get into multiple cities. That’s what I do all day, and I like it. It’s great.

I’m on my own right now. I don’t have a whole team, but it’s exciting. And hopefully, it works. I’m going to do my best.

What’s the best way for someone to contact you to learn more or follow up?

You can email me at ari@evarilabs.com, or reach out to me on LinkedIn. I’m pretty active there.

Is there anything else you’d like to talk about before we go?

I just think that, in many ways, the government gets a bad rap. There are good people who show up every day, working in government, doing their best for the citizens. But they should embrace technology.

The GovTech space is notoriously difficult. There are VCs who won’t even talk to people trying to do business with the government. And the reality is, the government is never going to release an RFP for the product I’m selling, because I’m the only one selling it—it’s not a known entity. I understand the point of an RFP. At Evari GIS Consulting, I spend my life chasing those kinds of opportunities. But in many ways, the government needs to figure out how to cut through bureaucracy and try new things.

It should be completely acceptable for a city to say, “Hey, Ari, why don’t you test this out on a neighborhood or 20 lights in a quiet residential area? Let’s see if it works.” And if it doesn’t work, so what? What’s the worst-case scenario? The streetlights turn on 10 minutes early or turn off too soon? We already deal with streetlights that don’t work all the time! Government should be way more open to experimentation and failure—the same way private industry is.

With that said, this fear of failure is also one of the government’s biggest weaknesses. There’s this mentality of “nobody gets fired for buying Apple products.” So in many cases, governments default to hiring the biggest, most well-known firms for consulting contracts. But in reality, it’s often their subcontractors doing the actual work. The assumption is that hiring a familiar name ensures a better product, but I don’t think that’s really the case. And I actually think it’s time that the government moves away from that mindset.

It’s time to look for innovative, younger, smaller teams that are building new things.

Want to learn more? Go more in depth here:

10 Reasons Why You Should be Using Data Driven Maps for Street Lighting Design

Leave a reply to Balloons that Cool the Earth: Resilience and Moonshots with Andrew Song of Make Sunsets – Mick Hammock Cancel reply